How COVID-19 Changed the Psychology of Investors

There aren’t any worldwide events that don’t have an impact on the way investors think. Every “black swan” event—defined as something we can’t predict in advance, but something that alters the economic landscape—will change us.

The COVID-19 pandemic is one such event. It’s going to change the psychology of investors, for good or ill. But while the pandemic is still affecting us, it’s difficult to predict how the psychology of investors will change in 2020, 2021, and beyond. What exactly are we going to do differently?

There are a few things we can glean from investor psychology and the emerging trends. While no one can say for sure how investors will change their behaviors in the future, we can point in certain directions based on what’s already happened. Here’s what we know about investor psychology—and what that might say about where investors are headed.

A Look Back: The Psychological Impact of the Great Depression

Many of us have grandparents who developed quirky habits during the Depression. Many of these habits lasted a lifetime.

“The Depression left emotional scars on the American psyche,” said one source. These fears last into today. “Whenever the economy sputters, as with the late 1990s dot-com fallout and subsequent recession, many people are gripped by fears of another Great Depression.”

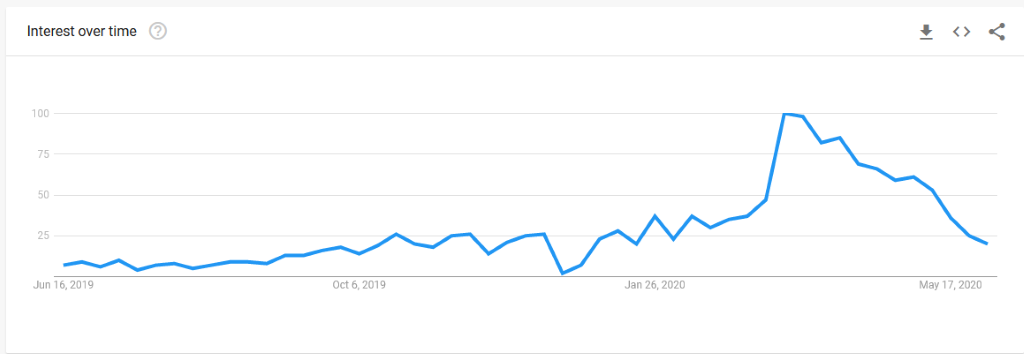

We can see that in Google Trends. As the COVID-19 pandemic spread, searches for “Economic depression” increased:

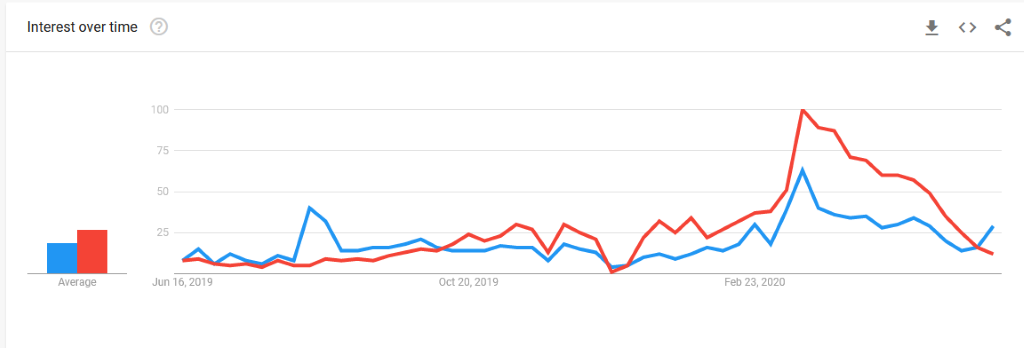

Although a recession is far more likely than a depression, we see that both of the search terms spiked at about the same time:

“Primacy and Recency”: Two Key Factors in Altering Investor Psychology

Daniel Crosby, a psychologist who serves as a behavioral finance expert, pointed out that there are generally two factors that influence our memory: primary and recency.

- Primacy is something that affects us because it was there when we started. For anyone who started out with real estate investing in 2007-2008, for example, you might expect that primacy to have a long-term effect on investing psychology, even if real estate has been stable since.

- Recency is a bias towards our most recent memories. We tend to remember what happened in the last year in the stock market, and this affects our thinking more than the years from 2010-2019, which are not as recent. This is a psychological effect that leads many people to ignore relevant data.

Says Crosby on the COVID-19 pandemic and its effects on the stock market: “But it will be especially impactful for those just starting out on their investment journey, who will have no other context for how the markets work. For them, all they will know is volatility and uncertainty and those lessons are likely to last a lifetime.”

For people who grew up during the Depression—an unprecedented event—“primacy” unfortunately worked against them. Who knows how much money some investors lost by keeping their savings in savings accounts, putting extra cash into coffee tins, or hiding it under the mattress? Unfortunately, with investment psychology, our experiences can color our perceptions even in real-time.

How Uncertainty Affects Our Worry and Fear

A study by UCL (University College London) once found that subjects who had only a 50% chance of electric shock suffered more worry than those who were certain they would receive an electric shock.

It’s easy to see how this might play out in the markets. For anyone who values certainty, they might view the stock market as “50% chance of having an electric shock.” You can see this in the headlines:

- Worry over whether there will be a “repeat” of the pandemic in autumn.

- Investors holding cash on the sidelines because they’re so uncertain about the future that they would rather make no returns than risk having negative returns in the short-term.

- Investors using stimulus money not to make new investments, but to shore up savings and/or pay off debt. We’ve seen many instances of consumers paying off credit card debt and making a small purchase rather than plugging their money into a new investment.

When Worry Hits the Streets, People Tend Toward Alarmist Thinking

There is an “alarmist bias,” according to economist Kip Viscusi, that results in people devoting “extra attention to the worst-case scenarios.” Viscusi studied this phenomenon in the late 1990s. The findings? People were more likely to dismiss more positive evidence about alarmist scenarios when conflicting evidence was presented.

Viscusi points out that media and advocacy groups tend to highlight the worst-case scenarios. That means that during alarming periods—like the COVID-19 pandemic—there’s a “selection bias” at work. Many investors are likely to see the worst-case scenarios and ignore any conflicting evidence. This is especially dangerous when there is an abundance of conflicting evidence that suggests investors should not take their money out of the market.

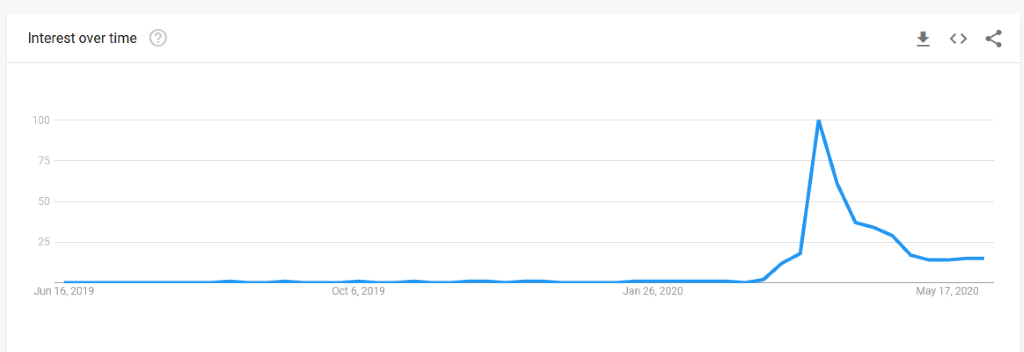

In the above, we see the Google Trend for “economic disaster.” Once again, we see a spike in searches as soon as COVID-19 made national headlines. Even as some worries went away, the underlying searches for “economic disaster” remain high above where they were in early 2020 and late 2019.

Loss-Aversion and New Biases in Investors

“I hate losing. I hate losing even more than I want to win.”

-Billy Beane, as quoted in “Moneyball”

“Loss aversion” is another major factor, according to author Jason Voss. Loss aversion is the psychological factor that means people feel losses more sharply than they feel the benefits of a similar increase.

For example, a 20% drop in the market will “hurt” more than a 20% gain will feel good. The aversion to loss might help explain some of the other psychological factors at play; selection bias tends to work against us. When investors are fearful that something bad will happen to the market, any evidence to the contrary is more easily dismissed. Meanwhile, stories about economic disaster will tend to prevail.

The above—“sell stocks” as a trend on Google—shows that even after the stock market started recovering, more people are thinking about selling stocks than they were before the pandemic. That’s even with the market showing the ability to roar back to previous levels.

Emotion Over Logic: How Many Investors Approach Money

One primary challenge that money advisors have, according to author Frank Murtha, is that investing can be a numbers game played on an emotional field. Wealth managers might prefer to take emotions out of it—to soothe investors’ anxiety by pointing to the very rational arguments to be made for continuing to invest. But this often fails to meet the emotional needs of investors. They may logically agree with what a wealth manager is telling them. But as long as their emotions are telling them something else, they can be hesitant.

How can investment managers better persuade clients about the best course of action? It means understanding that some investment decisions are driven by emotion. Rather than say that “we expect the market to do X and Y,” investors should speak directly to the long-term needs and goals of these investors.

Getting Rid of “Absolute” Thinking

As Michael Batnick of The Irrelevant Investor wrote, investors shouldn’t think in absolute terms—either being in the market or out of the market. He argues that investors tend to make major leaps during crises, which results in either-or decisions that investors never had to make.

“If you sold yesterday with the market down 10%, what do you today if it closes up 4%?” asks Batnick.

In times of uncertainty, one can’t blame investors who tend to move towards certainty—wherever they can find it. But the problem is that investors tend to move towards certainty by making drastic decisions that might not be the best decisions for their long-term goals.

How Investors Perceive Risk—and How That Thinking Might Be Flawed

A prominent 1981 study found that investors tend to perceive risk in one of three ways:

- Dread: The absolute fear present in an investor’s mind, especially when the future is uncertain.

- Familiarity: We perceive the familiar as being secure, even if more secure decisions may be unfamiliar to us.

- Number of people exposed: Although risk may be low, the more people are exposed, the more likely it is that we’ll reach wild conclusions about what’s about to happen.

COVID-19 inspired dread, was an unfamiliar threat, and had the potential to expose a lot of people to risk. Thanks to this “trifecta,” it weighed particularly large on the global psyche.

How to Relate to Investors Affected By COVID-19

- Realize that many investor decisions are emotional in nature. Finance is all about the bottom-line, but it’s impossible to ignore the fact that we’re all people with real fears and biases.

- Understand how investors perceive disasters and black swans. Black swan events will cause people to look for evidence that the sky is falling. Simultaneously, they’ll ignore the evidence that it’s not.

- Prepare for future crises by creating a plan of action for dealing with investors. Use the lessons you learned—and continue to learn—in COVID-19 to apply to the future.

Whether the future event includes new spikes in COVID-19 cases or simply a black swan event that no one foresaw, you’ll at least have a better understanding of investor psychology and why events unfold the way they do.